In the early 1980s, I got my first programming job and my first car loan. I was writing accounting software in compiled BASIC on PDP-11s, and the interest on my car loan was 17% per year. I still have a soft spot in my heart for BASIC, but only bad memories of the car loan, which sucked up a substantial part of the income I earned for writing the code.

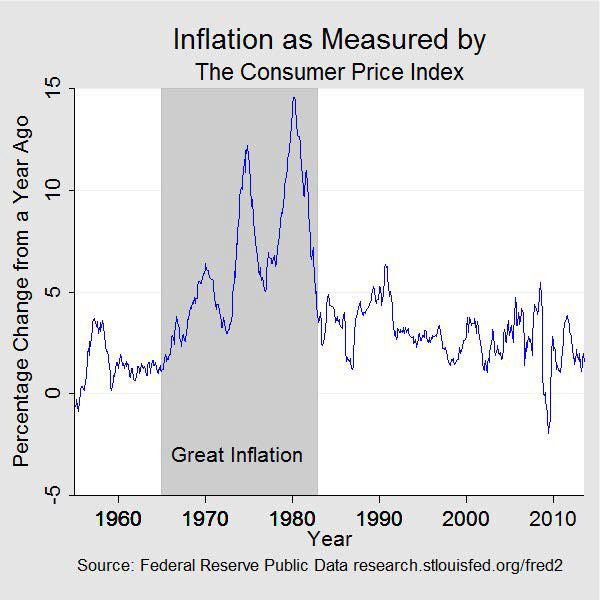

Many people reading this article will never have lived through an inflationary cycle. For decades, interest rates and inflation have been historically low, and inflation has not been a problem in everyday life. But now, the price of everything is climbing. A recent article shows inflation surging to over 6% after Q2 2021, compared to previous rates hovering at 1-3% for many years.

A few years ago, I wrote an article about how commercial open source was a good investment during recessions. Now, I'm wondering if it is also a good investment in inflationary cycles. And for many of the same reasons, I think it is.

What Causes Inflation

The schoolbook definition of inflation is too much money chasing too few goods. This is Economics 101 -- if people have money, and they want things, and there are not enough things, the market allocates goods among competing buyers by sellers raising prices. You may have noticed one part of this equation taking place already, as Uber raises fares trying to find more drivers willing to work, and supply chain shortages make electronics harder to buy -- so-called "demand pull"; inflation. The other part of the equation -- "cost push" -- is coming soon; the US recently passed a trillion dollar infrastructure bill, which is estimated to add $351 billion to the budget deficit. The arguments about whether unprecedented deficit spending will be inflationary are amusing, in a sad way. It almost sounds like our lawmakers are proving to us that our school system needs a better arithmetic curriculum. On the heels of the infrastructure bill are also likely to be new regulatory regimes that will further increase the price of goods.

In 2020, many people were concerned about the possibility of a recession due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Those fears were not exactly borne out. Instead, some industries boomed and some busted, but overall, the US economy weathered the pandemic better than anyone expected. However, even at the outset, many of us were concerned that the real cost of the pandemic was likely to be an inflationary cycle, which could be with us for many years to come.

The problem with inflation is that once it starts, it can be hard to stop, because people pricing goods build in cost-of-living accelerators. In the early 1980s, we experienced what is called an inflationary spiral -- prices go up, cost of living goes up, workers demand higher wages, prices go up, and the cycle begins again. In the early 1980s, the US Federal Reserve took extreme measures to raise rates, with the county enduring a deep recession before the cycle ended. Today, the only question about inflation in the near term is: how much, how fast, and will we be able to learn from the past to rein it in?

So as they say, fasten your seat belts, it's going to be a bumpy night.

Commercial Open Source

Open source has become a common business tool only over the past 30 years or so, and, luckily, these years have been historically free from inflation. So, unlike my prior analysis of open source as an investment in recessions, this one can't be empirical, and we need to reason from first principles.

-

Efficient use of capital. COSS saves capital costs in two ways, compared to other businesses. Efficient use of capital is always important. But in inflationary periods, it is even more important, because interest rates rise. There are various causes to this -- among them the expectation of higher prices, which is part of the basis for the inflationary cycle. But there are fundamental causes, too. Higher budget deficits will mean higher interest rates, as federal bonds issued to cover deficit spending compete with other investments in the capital markets. As capital becomes more expensive, startup businesses lose viability and fail, or simply can't deliver high capital returns.

- Lower Overhead Costs. COSS businesses have a lower marginal cost of sales than most other emerging technology businesses. Open source licenses can save significant costs of sale, because open source products often develop a following by word of mouth with little or no formal sales activity. Also, open source licenses -- even copyleft licenses like GPL or AGPL -- can serve as proxies for evaluation licenses that would otherwise have to be negotiated and reviewed, resulting in transactions costs for business development and legal staff.

- Less Capital Burden. Even setting aside these cost savings, COSS businesses are often started successfully (achieving "project-community-fit") with often very little to no capital invested in a business, for months or even years. Every business needs to prove out its market, and will only succeed if it reaches economic sustainability before the investment runs out. COSS businesses can develop key indicators of success even with little or no hard costs. Or better said, the investment is often primarily the "sweat equity" of the founders, who can gain enough traction with no investment, quickly enough to attract outside investment as needed. In contrast, other businesses can require infrastructure, offices, or significant time to prove their business case, resulting in higher capital outlay.

- Cheaper products. In inflationary times, every buyer -- from individual user, to CTO, to the procurement departments of a company -- is looking for a bargain. Open source products tend to be less expensive than their proprietary counterparts, resulting in increased market share. A widening gulf in prices of proprietary substitutes also means that buyers can afford to expend some costs in switching from proprietary to open source software, in exchange for long-term cost savings. Inflationary times are the opportunity for COSS businesses to show their competitive advantage.

- Pure Intangibles Don't Suffer from Demand-Pull Inflation. This one is a little complicated, so bear with me. There is a difference between an open source project and a product. Open source licenses are just grants of rights. They are so-called "pure intangibles." Products made with open source software -- even so-called pure open source products like a Linux distro -- are not pure intangibles. Creating them incurs some costs, like for build engineers and maintenance and support teams. Open source code is free of cost* and free of charge. And the thing about free, is that 110% of free is also free. So assuming a COSS business uses its open source releases to leverage sales, those releases will not need raised prices to allocate them. Accordingly, even if the COSS business' products lose some customer base due to demand-pull, the open source project doesn't. This means the COSS business may be better able to ride out an inflationary cycle than a proprietary software / "closed-core" business. Even if sales of its commercial products lag, the open source project will maintain a stake in the ground to preserve community and market share.

The good news in 2021 is that interest rates have been so low in recent years that there is a lot of room for monetary policy to put the brakes on an inflationary spiral. Also, today, our data is better, we are no longer tethered to a gold standard, and our understanding of monetary policy is more sophisticated than ever. Perhaps the AI that will be used to address monetary policy in the coming years will come from the very open source projects that survive the cycle. But in the meantime, inflation hurts, as anyone who has lived through it can tell you. It hurts consumers and it hurts businesses. As they have in the last few recessions, open source businesses are poised to endure this pain better than most.

* To be precise, there are some costs to distributing open source code, like serving downloads, but they are tiny in comparison to most cost-of-goods analyses.

If you want to learn more about the Great Inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s, which has been called the defining moment of the economy in the late 20th century, this is an excellent article: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation. This article does not discuss Nixon's wage/price freezes of 1971 and 1973, which failed to curb inflation, probably because they focused on demand-pull and cost-push, and did not properly take into account the effects of monetary policy.

Top comments (0)