When markets are on an upward trajectory, investing is not so hard. After all, the stock market always goes up over the long term. But it takes more work to identify good investments during down markets. Fortunately, COSS businesses can be a great investment during bad times.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence for this premise. First, the demand curve. Linux was getting popular before 2001, but its popularity skyrocketed during the Internet bust. That shows the power of COSS on the demand side, and it fits a classic demand curve analysis. When times are bad, and profits are down, buyers turn to lower-cost goods. In addition to being a more capital efficient model, COSS is often developed as a substitute for costly proprietary software. IT managers tasked with cutting budgets turned to COSS in earnest beginning with the downturn of 2001.

But the economic profile of COSS is also about the supply side. In difficult times, the companies that use capital most efficiently survive. COSS companies are fundamentally more capital efficient at running on and innovating with far less capital, and that makes COSS one of the most interesting investments in a down market.

COSS companies leverage capital efficiently for many reasons. First, consider the people who write OSS. Today, even though OSS is heavily underwritten by industry (large tech companies, but also any company employing software engineers at large), an OSS project is still usually the brainchild of an individual or small team who came up with the idea on their own and had no top-down direction to create it. So, the roots of most projects are still in the garage. That means the labor to make the initial development sprint is usually a volunteer effort. This can play out in different ways. Perhaps an engineer starts a side project while employed doing something else. Perhaps an engineer expends time during slow periods, or while between jobs, to create a resume trail, network, or prepare for the next opportunity. The cost here is the engineer’s sweat equity — definitely not a zero cost. But it is, undeniably, an efficient cost. No expensive office lease, no free lunches, no swag. Just work.

Once a project is underway, it gets a slew of free marketing advice from adopters who vote with their feet. Downloads are not dollars, but downloads can tell you a lot. Is the project going in the right direction to meet market and user needs? Is it reliable? Is it structured correctly? Are its goals and its value properly communicated to the community? As they say, criticism is a gift. All this feedback is a trial by fire. Any OSS project that comes out on the other end of its initial pipeline alive has been road-tested in the most ruthless way imaginable.

There are also efficiencies in ongoing maintenance, but this can be a red herring. Many focus on the most obvious benefits of COSS — that the world is your maintenance, support, and extended engineering team. But that is the bean-counter viewpoint, and the real efficiency has more to do with the costs of a mature project versus a nascent one. It’s also misleading. In truth, most OSS projects are primarily maintained by their core committer team, and the value of community input is primarily in feedback — bug reporting, feature requests, and evaluation. In fact, projects like Linux that have a wide and active community of committers vying for PRs is the exception, not the rule. So if you find one of those, it’s probably a great investment. But until that unicorn comes along, there are plenty of projects with great potential that don’t “outsource” their support to the community.

If we take all the above as a given, a COSS company makes incredibly efficient use of resources in its early stages. Now, suppose you are an investor looking for your highest long-term multiple. Consider that a COSS company does not usually get formed on day one of this process. It usually gets formed after all this initial honing has taken place (only 15 ~ of 40 — see columns B and C — COSSI* companies were founded at the same time or after the core OSS project was released)*. So, if you have a choice between investing in a fledgling COSS company, and a proprietary company, that choice is simple. The proprietary company will be using your capital for initial development, feature definition, and road testing — not to mention the financing roadshow. The COSS company already has a foothold on its product and market. So, at a minimum, investing in COSS companies takes place at a better inflection point than for fully proprietary companies.

But that is theory. Now we have to road test this hypothesis: Do COSS companies survive downturns well? The analysis below suggests that the answer is a resounding: Yes.

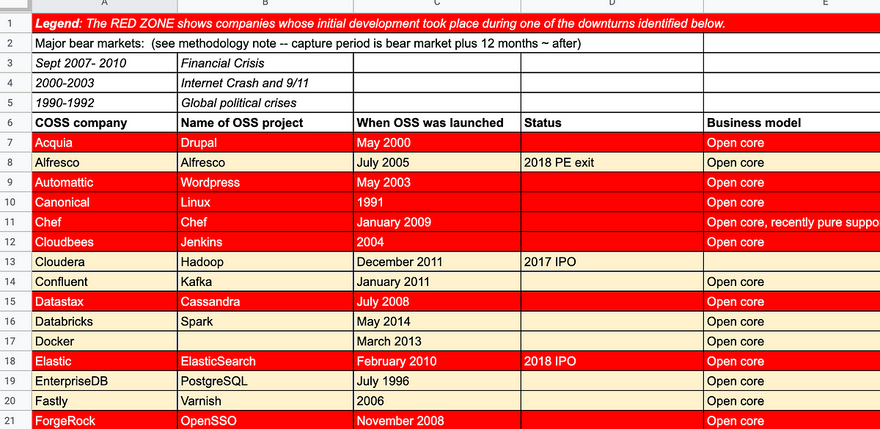

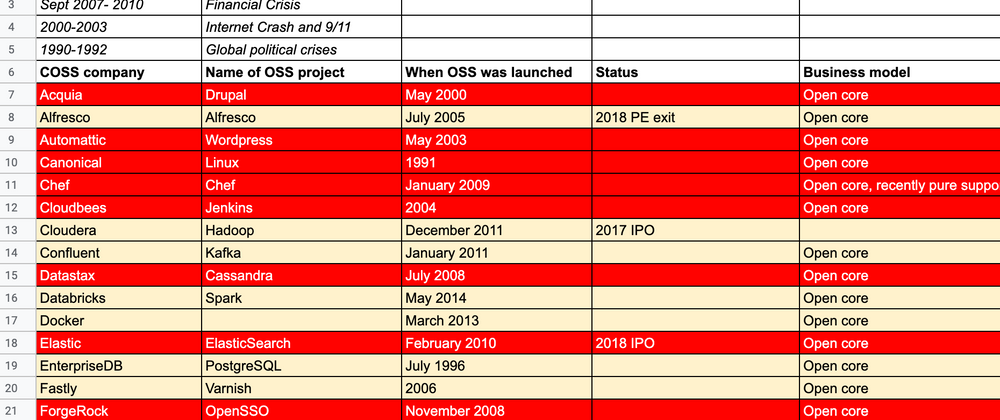

To investigate this proposition, we looked at approximately 50 ~ COSS companies. These included notable exits and companies with a notable business.

Then we identified the major down markets of the last 30 years.

Our working assumption was that OSS development would have started in the 12 months prior to the first release. So, we included in the RED ZONE companies who released in, or within 1 year after, a down market.

The results speak for themselves — most of the biggest COSS companies were built on software developed during a downturn — even if we eliminate the Linux distros. Of the companies considered, over 60% of them were started during a recession.

We are excited for whatever comes next. If the market is great, there will be lots of winners. If not, we will be following the winners.

Here is the link to the data: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/154cATlIe5VHMlYa0U1sa5VSLM_VTVi5zWdCIQas8VQY/

The exceptions are also notable — the wave of acquisitions by Oracle in the 1990s and 2000s, Kubernetes, Docker, and several Apache projects during the past 7 years since the recession of 2008.

Now, to be scientific, we would have to also pick a control group, but we haven’t done that. To be candid, this is like one of those clinical trials where they stop the control group for moral reasons once the initial data comes in. We don’t need to know if proprietary companies would do as well — we don’t think that’s likely. But even if so, the more efficient capital use by COSS companies greatly excites us.

Capital, thoughtfully applied to COSS businesses in bad times, is a big countercyclical advantage.

Methodology

The selection of 50 ~ companies was to some degree arbitrary, in the sense that we applied a few rules to identify COSS companies (who directly capture value from their OSS) according to our definition. We did not include companies like Facebook or Google who contribute greatly to open source development, but whose primary business (indirect value capture) is not open source development. In other words, primarily proprietary companies with open source activities. We excluded the blockchain/cryptocurrency world given the economics and primitives involved are highly orthogonal to COSS companies who focus on building and selling a product to enterprise customers as a service or packaged offering — other methodology notes appear in the table.

75% (30 out of 40) of OSS projects behind COSSI companies were started during recessions

Finally, in applying this analysis to our COSSI data, 30 + out of 45 of the OSS projects behind COSSI companies were started during recessions.

The 10 companies/projects that were not started during recessions: Alfresco, Confluent (Kafka), Docker, ForgeRock (OpenSSO), GitHub (Git), Instructure (CanvasCMS), MySQL AB, Puppet Labs and Sourcefire (Snort).

Based on the current snapshot valuation of COSSI overall, this group of companies represents about $20B in value captured relative to the $150B total across all 45 ~ COSSI companies today.

Top comments (0)