In this post, we aim to:

- Define what it means to be a COSS (commercial open-source software) company.

- Propose that COSS is sufficiently unique, complex and misunderstood to justify its own classification.

- Outline and examine key differences between FPS (fundamentally-proprietary software) companies vs. COSS companies.

Motivating COSS

At the extreme, there are exactly two kinds of “software companies”:

- Fundamentally-proprietary software (FPS) companies: These companies encompass the spectrum of what the industry classifies as COTS, SaaS and more. Examples include old-guard behemoths like SAP, Oracle, Software AG, SAS Institute, etc…companies like Workday, Salesforce, Adobe, ServiceNow…and new-blood names like Twilio, Stripe, Atlassian, Airtable, etc… Today, “FPS” is the dominant company building model across all layers of the stack, including IT infrastructure/middleware. FPS companies likely structurally represent ~90%+ of all software companies.

- Commercial open-source software (COSS) companies: These companies fundamentally depend on a singular core (exactly one (1) in the vast majority of cases, but sometimes 2–3) open-source software project to justify their existence. Said differently, if the core OSS project did not exist, the company would not exist (the converse is not true). Herein lies the simple definitional ingredient of a COSS company (agnostic to tech, business model or other factors). Examples: Elastic, Inc. would not exist without ElasticSearch, Cloudera would not exist without Hadoop, Pivotal would not exist without Cloud Foundry, GitHub/GitLab would not exist without Git, etc. 40~ more examples of successful COSS companies are listed here.

We believe that COSS companies are, fundamentally, *functionally different in nearly every way *(example functions: sales, strategy, product management, marketing, engineering, hiring, finance, legal, etc.) as compared to FPS companies.

THREAD: At @OSSCapital, we strongly believe commercial OSS companies are fundamentally different in nearly every way functionally as compared to proprietary, fully closed-source software companies of the past. However, in what ways are they specifically different? Let’s explore.

— Joseph Jacks (@asynchio) November 1, 2018

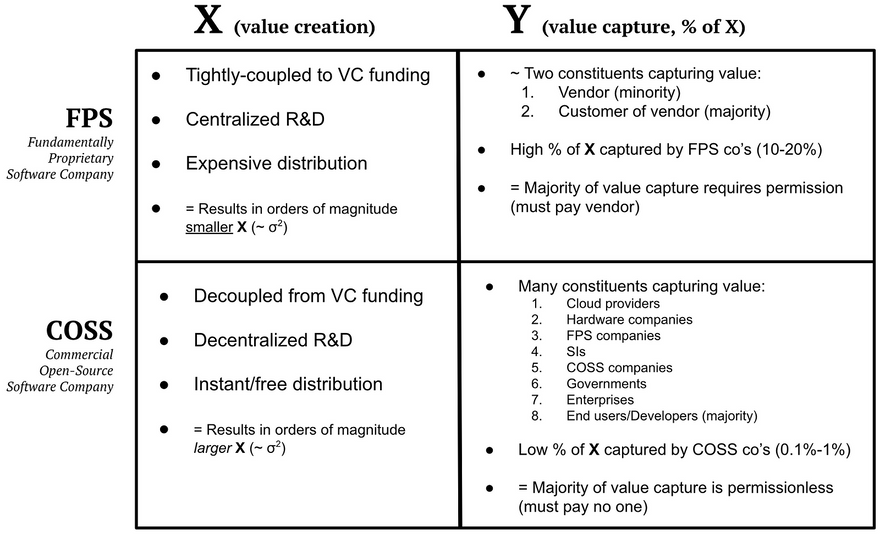

In the the following chart, we explore the key foundational aspects that serve to explain why COSS companies are, in fact, fundamentally different from FPS companies from the lens of their respective value creation inputs and value capture outputs:

X and Y express two independent variables that each measure economic value creation (X) and value capture (Y, measured as a % of X).

Importantly, the inputs affecting the size of X and the **share **of Y are completely separate from each other.

To further clarify the intent and focus of this framing, the properties in this comparison matrix are meant to be used as a general and abstract framework-oriented way of considering how successful FPS companies (regardless of business model, distribution model, etc) create and capture value. The same is true for COSS: this assumes a given COSS company is a successful example (one based on an open-source software project(s) with a high propensity for large scale — $100M+ revenue potential — industry commercialization).

FPS value creation and value capture (top row):

With FPS company value creation (~exponent of X, top left), in nearly all cases (by one standard deviation, potentially squared based on the core inputs we list), in order to create significant value, VC funding is typically needed to build the product…even more capital is needed to distribute the product to customers and users…and even more capital is needed to capture value when selling the product and scaling operations (distribution). Another huge input to value creation is R&D (hard engineering output, product development, etc) — this is almost always fully centralized inside the “four walls” of a given FPS company — meaning that the FPS company must employ or pay a software engineer in order to change/upgrade/improve the codebase of the core offering/service/product. As a consequence of just these three key dimensions (funding, R&D and distribution), we believe in the vast array of cases that the exponent of X (by one standard deviation, potentially squared based on the inputs) for FPS companies is orders of magnitude smaller vs the X potential of COSS companies — explained more below.

With FPS company value capture (top right), there are vastly only two primary constituents capturing value: 1) the vendor who created the software, and 2) the customer (basically representing any constituent) who must pay the vendor to use/access the software. Intuitively, we believe that the vast majority of value created by FPS companies is captured by customers paying to use the software in some way (80–90% of value being captured by the customer). However, the remaining share of value, a large share, is captured, we believe, roughly on the order of 10–20%, by the FPS company. Why such a high %? If the following is true, this is likely to be roughly accurate: If an FPS company builds a product and somehow convinces a customer that the product (regardless of how it is consumed as a service, on-premise appliance, network service, etc) saves a given customer X dollars or causes the customer to be X dollars more innovative/efficient, then Y % of those economic dollars are the rough “market price” for what the customer ends up paying to the vendor in exchange for use of the software — roughly speaking, this is how we end up with estimating 10–20% captured by the FPS vendor if a given company convinces a customer they are $5M more innovative or were able to save $5M in costs, they could then potentially capture ~$500K–1M in LCV. Crucially, in order to capture value, a given customer must have permission from the FPS vendor (even with freemium models, which are very different from open core — the predominant commercialization model of COSS companies).

COSS value creation and value capture (bottom row):

For COSS company value creation (bottom left), value creation is completely unbounded from funding. R&D is totally decentralized (most of the time). Distribution is free/instant. Significant value creation often occurs well ahead (in some cases, many years) of company founding (compare columns B and C in the COSSCI). R&D is, in most cases, decentralized far beyond the four walls of the company. As a consequence of these two properties (decentralized innovation and unbundling from funding constraints), we strongly believe that the exponent of X (again, by one standard deviation) with COSS companies is almost always orders of magnitudelarger than the X of FPS companies.

For COSS company value capture (bottom right), the story is quite different when compared to FPS. Instead of only two constituents capturing value, there are many. We believe the vast majority of the value captured in the COSS “Y” is captured by end users/developers using the software — the rest (maybe 10%, at most) of the value capture is disaggregated across many other constituents: Clouds (AWS, Azure, GPC, etc), COSS companies (Cloudera, Red Hat, Elastic, Confluent, etc), FPS companies (Oracle, SAP, etc), Hardware companies (Apple, IBM, etc), Consumer internet companies (Facebook, Google, etc), Enterprises (Wells Fargo, Walmart, etc)… basically any company using software today uses open-source software, so this list is quite long. Again, crucially, the key distinction here is that COSS constituent value capture is completely permissionless — and we believe this fact is a very good thing.

Conclusions

There are many ways of looking at and making conclusions from these fundamentals, but we believe the following things are true:

- COSS companies can and should successfully commercialize by maximizing X, not by maximizing their share of Y (non-compete/discriminatory licenses only serve to do the reverse).

- COSS companies are fundamentally different from FPS companies.

- COSS companies are fundamentally more capital efficient in terms of how they create far more value than FPS companies.

- FPS companies capture more of the value they create vs. COSS companies but they almost always create orders of magnitude less value than COSS companies/their core projects create.

- FPS companies can capture more value (perhaps ~10–20%) vs. COSS companies (perhaps only ~0.1%-1%), but successful COSS companies always create orders of magnitude more value in the world vs. FPS companies, thus even if COSS companies capture a tiny slice of the Y, they can become multi-billion dollar software companies as evidenced by the growing COSSI dataset, a list that has been doubling every year since it was created in early 2015. We expect there to be many hundreds of COSS companies on the COSSI sheet over the coming years.

COSS is the Future

We believe that over time (decades), all FPS companies will shift and gradually evolve towards becoming COSS companies — given the fundamentally superior economics of COSS value creation.

Additionally, we expect more new software startups that are founded will start as COSS companies and embrace this model from the beginning.

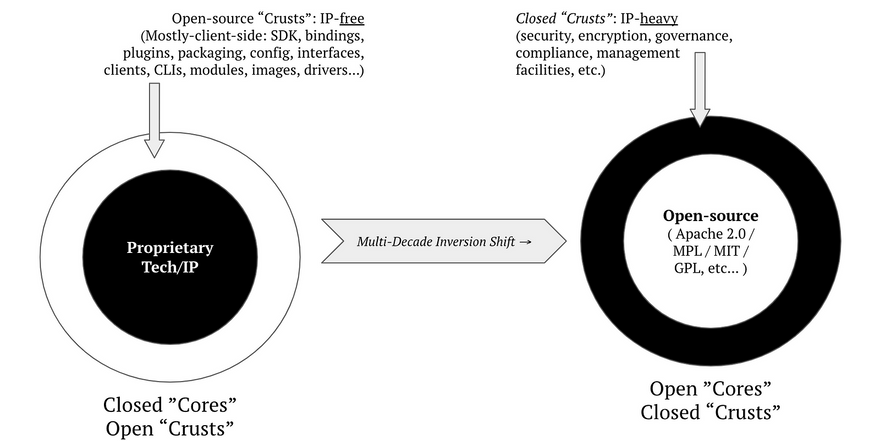

One potentially helpful way of reasoning about this (in perhaps an overly simplified manner) is that the “core” of **nearly all **FPS companies today is closed (proprietary — IP/patent heavy) while the “core” of COSS companies is open (OSS — “IP” free).

We visualize this distinction below:

Nearly every FPS company has a GitHub page with examples of these “open crusts” — here are a few examples of FPS companies and their open crusts:

- https://github.com/SoftwareAG

- https://github.com/Oracle/

- https://github.com/SAP

- https://github.com/Twilio

- https://github.com/Proofpoint

- https://github.com/Stripe/

- https://github.com/Adobe

- https://github.com/VMware

On that note, we’ll end this post with some data points on the largest FPS company in the world (Microsoft) itself gradually evolving towards becoming a COSS company:

OSS eats everything & COSS is the future of the software industry. PROOF: @Microsoft, world’s largest software company founded in 1975, historically an aggressive fundamentally-closed bastion of proprietary IP + patents did the following ALL over past 5 years, mostly in 2018 💥 pic.twitter.com/cat4jJ5Ua1

— Joseph Jacks (@asynchio) January 8, 2019

Thanks to the following people for providing generous varied feedback and contributions on working drafts of this post: Kevin Wang, Nick White, Heather Meeker, Dave Patterson, Syrus Akbary, Sijie Guo, Ian Tien, Haseeb Qureshi, Dave Lester, Karthik Ramasamy, Jeff Meyerson, Mark Burgess, Petar Maymounkov, John Komkov, Yves Junqueira, Jim Walker and Luke Kanies.

Top comments (0)